The establishment of the US Army’s Fort McKinley on Great Diamond Island was part of larger effort by the government to provide strategic harbor defenses throughout the country at the end of the 19th century. The 200 acres on the northern half of the island was the largest of four Maine coastal forts.

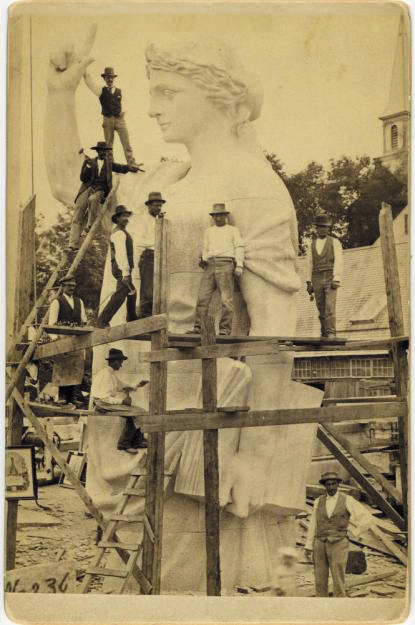

Constructed in 1910, and housing 200 soldiers, the Double Barracks was the largest of 5 barracks built to house the enlisted men. It sits at the north end of the parade ground, and is the only remaining double barracks at the Fort McKinley complex.

The threat of a major attack diminished greatly by the early 1940s and the government halted the build-up of coastal defenses by 1944. Modern warfare tactics of WWII contributed to make existing harbor defenses obsolete, and the government dissolved the Coast Artillery in 1950 and abandoned the forts.

These properties were first offered for sale to state and local governments at undervalued prices before being sold to private interests. Fort McKinley passed through several owners before Bateman Partners acquired the property in 1993 and began efforts to revitalize the property into a resort community, building by building.

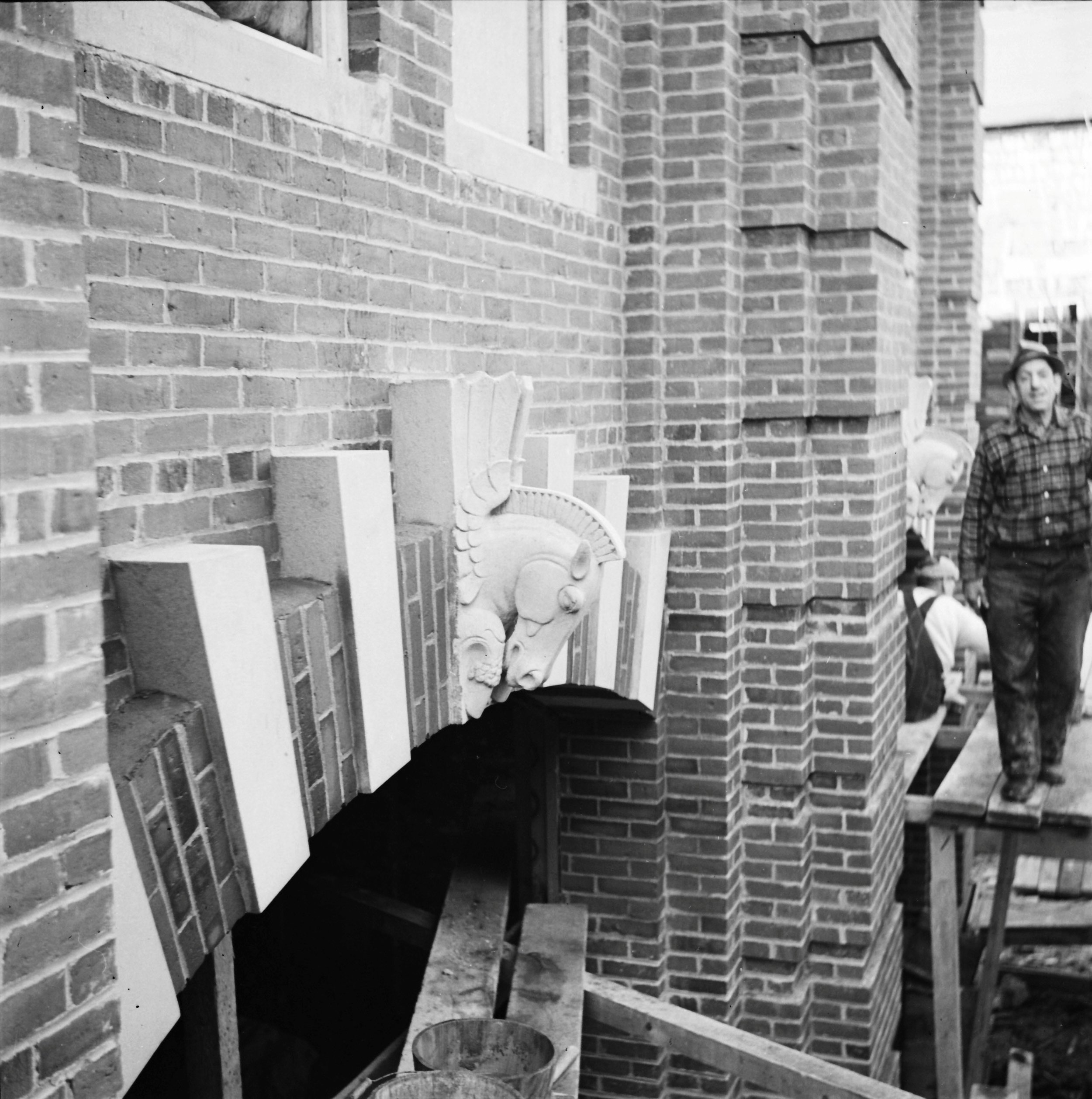

The double barracks needed major structural repairs due to water infiltration and decades of abandonment. When the project was 95% complete, a fire broke out and burned all of the interior structure. The brick exterior was all that was left standing. Working with the National Park Service and the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, it was determined that Historic Tax Credits could help the project rebuild.

This decision for salvaging the exterior and reconstructing the rest of the building preserved the physical memory of the double barracks while rehabilitating the space into functional resort inn.

This project defied all odds, transforming a collapsing building into an intrinsic part of the Fort McKinley historic complex.