The revitalization of the Abraham Robinson Block, by East Brown Cow, brought together industry experts exemplifying a deep-rooted appreciation for local history and culture, with an eye towards the building’s future stewardship and its contribution to the vitality of Portland’s Old Port neighborhood. The commercial block, having been built as an anchor of the vibrant Jewish Quarter in the early 20th century, will now carry on the legacy of one of Portland’s early immigrant communities.

In 1911, Russian Jewish immigrant Abraham Robinson purchased the property on Middle Street after building his business from a roadside cart. At the time, the lot contained a one-story wood commercial building, a duplex tenement, and a brick house. In 1914, Robinson constructed the current commercial block to house his clothing store on the first floor, flanked by a grocery store and drug store. The upper floors included factory space and a social hall, known as Robinson’s Hall. The hall hosted dances and meetings of labor organizations like the Hod Carriers and Building Laborers #12 and the Portland Lodge of the Jewish organization B’nai B’rith. The upper stories were later adapted for manufacturing and continued this use until Robinson lost the property during the Great Depression. Myer and Esther Goldberg purchased and operated Model Foods Importers & Market on the first floor, importing foreign foods from around the world to Portland. East Brown Cow acquired the property from the Goldbergs in 1998, reactivating the unused upper floors as office space.

In exploring how they could rethink the underutilized Abraham Robinson Block, East Brown Cow looked to capitalize on its historic character. Preservation consultant Scott Hanson worked to extend the National Register-listed Portland Waterfront Historic District to include the history and architecture of the commercial block, which provided eligibility for state and federal historic tax credits. The design team, including Mark Mueller Architects and Ealain Studio, zeroed in on existing elements such as the tin ceilings and wood flooring, while reintroducing details lost to time.

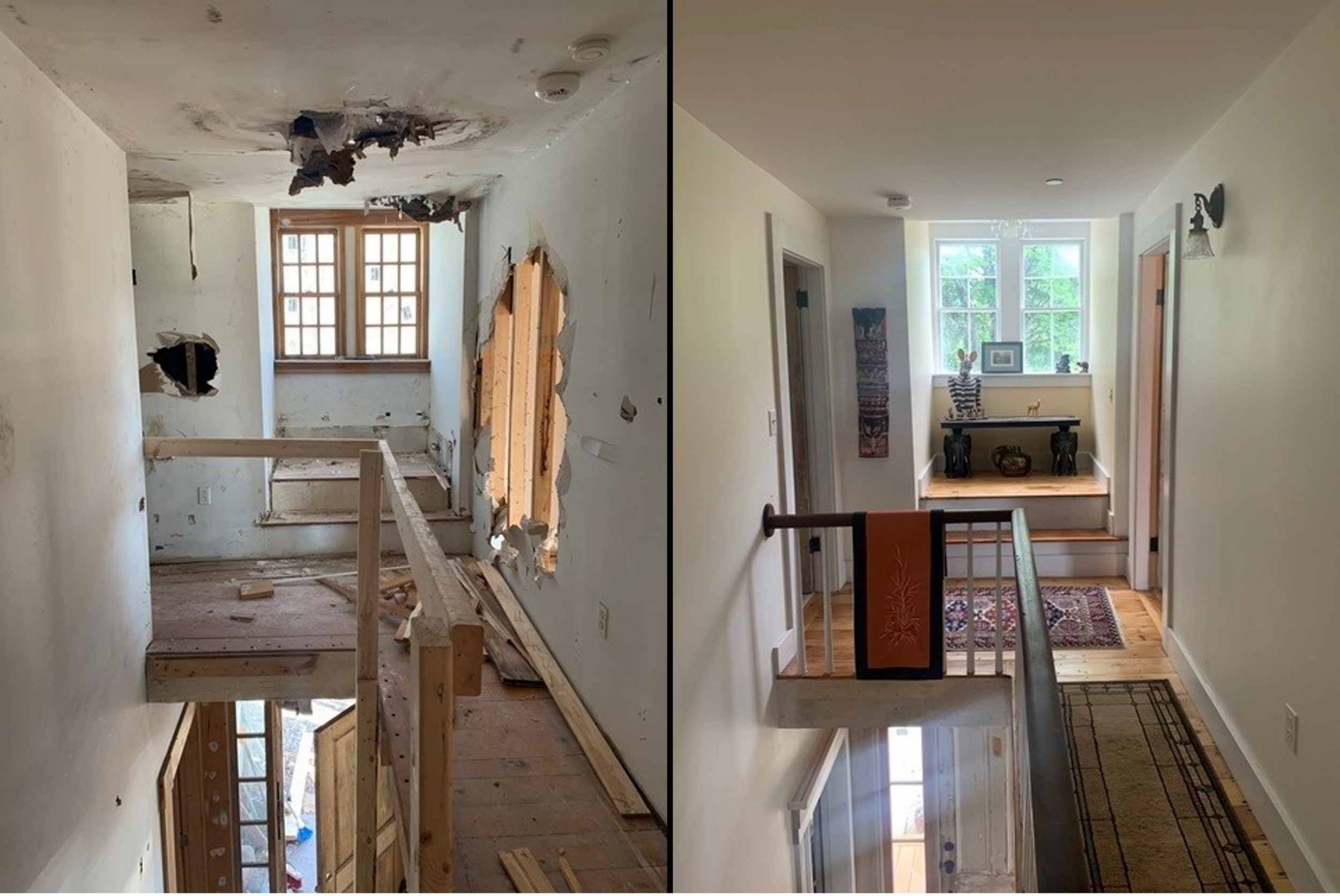

A major component of the project was restoring the tin ceilings throughout the second floor, which required careful abatement of lead-based paint. To fill in gaps in the second-floor ceiling and reintroduce the tin ceiling on the third floor, East Brown Cow turned to the experts. W.F. Norman Corporation, a centuries-old company that specializes in tin ceilings, constructed identical molds based on the original pattern. Trusted partner, Monaghan Woodworks, executed the challenging re-installation of the ceiling within the trapezoidal structure. Monaghan also restored the original beech flooring, seamlessly integrating new wood to the match the species and appearance of the original.

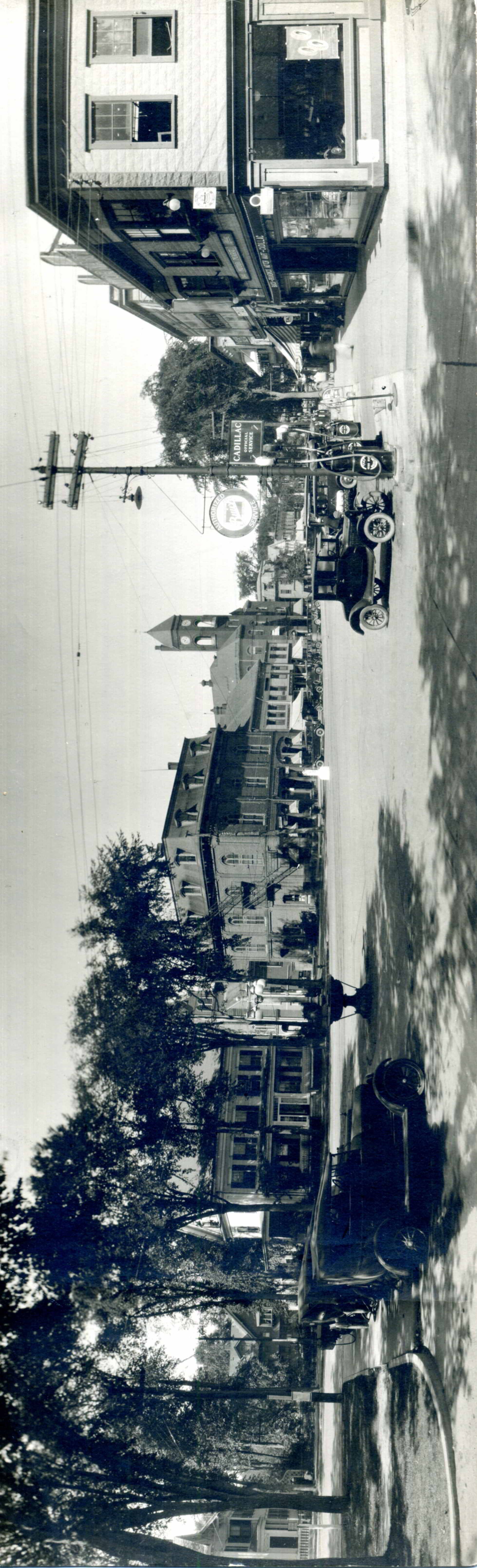

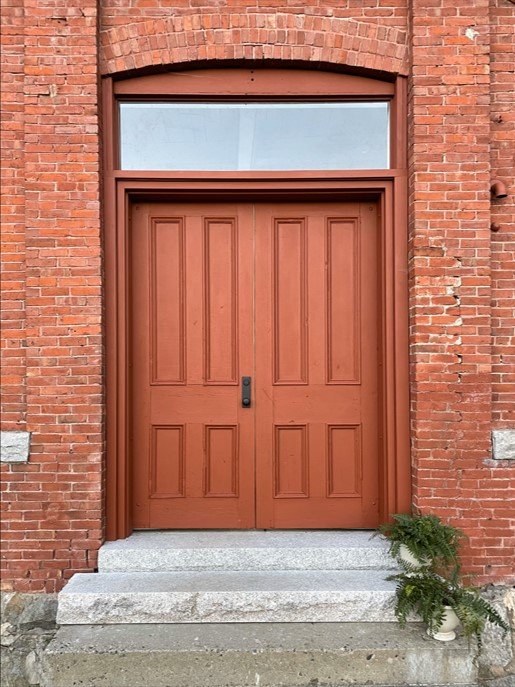

Through research on Middle Street storefronts from 1924, local craftsmen at M.R. Brewer fabricated a new door and surrounding millwork to match the building’s original design. Historic paint analysis guaranteed a color match of the original façade. Best Dressed Signs created an era-appropriate, gilded entry sign based on a historic image. New roofing was installed and leaded copper was used to recreate historical details missing in the cornice.

While retail continues on the ground level, the second and third floors have been revitalized into modern “Urban Homes.” These three-bedroom, distinctive hotel stays honor the original character of each space, providing a glimpse into the history of the Old Port for visitors, just steps away from local boutiques and renowned dining.