In Norridgewock, along the eastern bank of the Sandy River, what was once modern and critical infrastructure had become obsolete, and its reuse would take some imagination and a determined effort.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Board of Electric Commissioners and Madison Village Corporation voted to develop water power along the river’s French Rips. They commissioned local architecture and engineering firm Snow & Humphreys for design work and Hall & Reed completed construction in 1904. The site included a powerhouse, along with a 300-foot dam, intake canal, and open-flume intake structure.

A little more than 100 years later, the Madison Electric Works station was generating less than 2% of the town’s electricity, and a desire to restore salmon, American Eels, and other sea-run fish in the Kennebec River Basin prompted removal of the dam. The powerhouse was spared, but it quickly fell into a cycle of neglect and vandalism.

While searching for a small, historic industrial building to transform into her home, Amanda Lamb learned about the powerhouse and closed on the property in 2017. Little did she know the herculean task that lay ahead. The 1,400 square-foot building provided a blank canvas, but much work was required to make a livable space. The original wood floors had been irredeemably damaged by the removal of the turbine and other heavy equipment, and the interior walls were covered in peeling lead paint. The industrial building had never required plumbing or a heating system. All nine existing windows were in need of a full restoration. Among the toughest challenges, would be the 14-ton generator left behind by Madison Electric Works which occupied nearly a quarter of the space.

Shortly after starting the work, Amanda encountered an unexpected hurdle. The town issued a stop-work-order due to zoning and flood plain issues. After attending every planning board meeting for a year – even less glamorous then abating lead paint – Amanda secured the permissions needed to proceed. She now counts the Norridgewock Planning Board, Town Manager, and code enforcement officer among the allies that made the project possible.

Amanda proudly tackled a lot of the work herself, calling upon talented friends for help. She engaged professionals for specialized tasks including pouring concrete, trenching, propane installation, and stonework. James Pollis, a local plumber and electrician, was among those that helped.

After slow and steady progress, drilling through three feet of granite foundation to introduce plumbing to the building for the first time in its 100-year history felt like a turning point! Build out of the bathroom and kitchen followed, as well as installation of a radiant heating system. A new concrete floor and fresh coat of white paint on the walls and ceiling brought the space together.

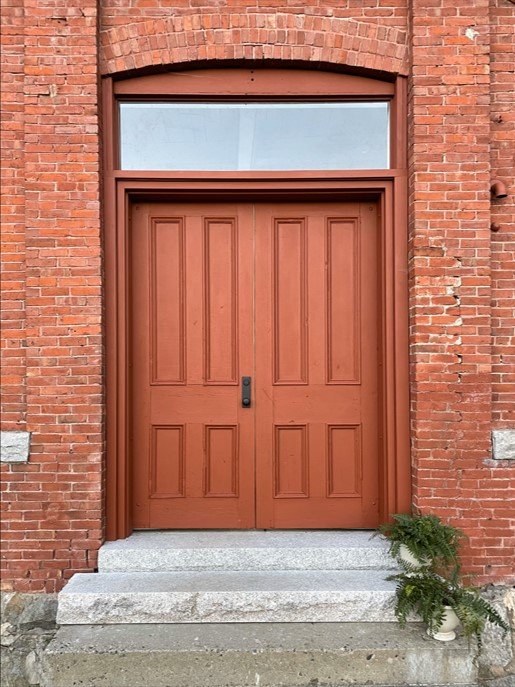

The final task was finding entry doors, as the originals were lost to a flood in 1987. Keeping with the industrial spirit of the building, Amanda salvaged replacements from a mill in Biddeford. After five years of hard work, determination, and a few too many public meetings, the River House was complete.

With recognition of this project, Amanda hopes others will be emboldened to revive forgotten industrial buildings for their own use, also benefiting Maine communities. Having been a recreational spot for so locals over the years, Amanda still allows river access for fishing, boating, and swimming, which also provides an opportunity to show folks the repurposed powerhouse in all its glory.