The Story

The story of Sugarloaf Ski Mountain began in 1950 when the Sugarloaf Mountain Ski Club negotiated a 20-year lease with Great Northern Paper Company for land on the mountain. In the subsequent years, Winter’s Way was laid out (named in honor of local organizer Amos Winter), a base hut was constructed, a rope tow installed, new trails were cut, and T-Bars were added to allow skiers increased access to the mountain.

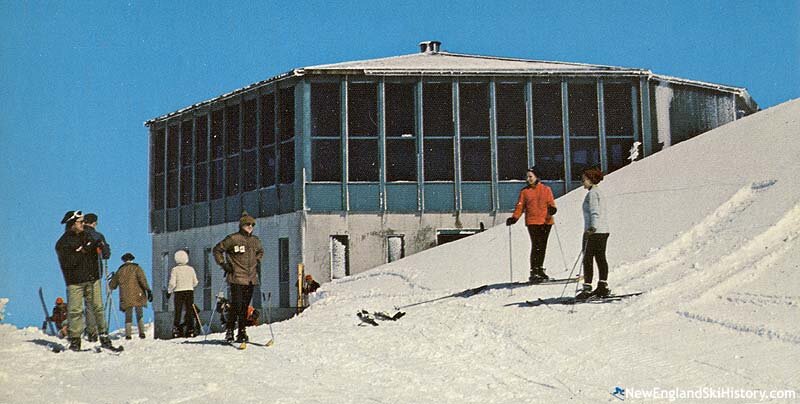

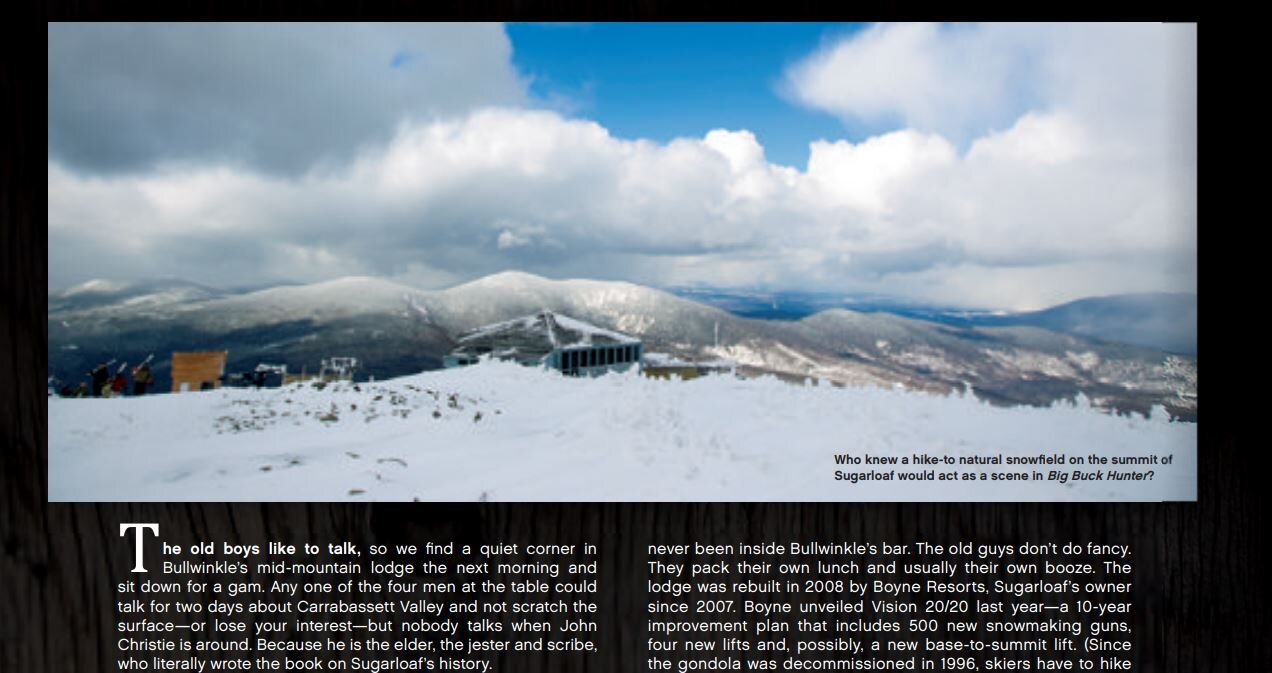

In 1964, a lift line was laid out from the top snowfields to the bottom of the mountain. The decision to buy a two-stage gondola from Cologne, Germany would transform the mountain, and it was rebranded as Sugarloaf/USA. Entering into the international ski scene, it became widely known as “The Mighty Gondola.” The midcentury modern hexagonal Summit Lodge was completed in the 1966-1967 season, just in time for Sugarloaf to host the NCAA intercollegiate skiing championship. The modern lodge marked the high point of the beloved ski resort.

Unfortunately, the gondola declined in operational capacity following an accident in 1986 until it was closed permanently in 2000. The gondola cars were sold at auction and can still be seen around the valley as a reminder of the mountain’s glory days. The lower station was replaced by the Alfond Competition Center, and various gondola parts are still scattered in the mountain woods.

The Summit Lodge was once open to Appalachian Trail backpackers as a night shelter–a dry place to escape the weather with amazing views. This continued even after the lodge was closed to skiers in the winter. Due to vandalism and mold the lodge was finally closed in 2009.

The Summit Lodge remains atop the mountain at the terminus of the phantom gondola lift. It sits vacant as skiers disembark the nearby Timberline chairlift, and swoosh past the once vibrant Summit Lodge.

The Threat

Vacant for two decades, the highly visible Summit Lodge is in need of repairs and a new lease on life. Sugarloaf 2030 envisions the next ten years on the mountain with plans for the Summit Lodge included in 2030’s “late stage,” to be completed between 2026-2030. This plan is for the transformation of the site which may include demolition of the Summit Lodge, stripping the mountain of an architecturally significant building and a piece of Sugarloaf history.

How to Get Involved

Let your voice be heard by Boyne Resorts, the owners of Sugarloaf. The demolition of the Summit Lodge will cost several hundred thousand dollars, which could be invested in rehabilitation instead.

Click here to view Sugarloaf’s 2030 plan, including public information meetings.