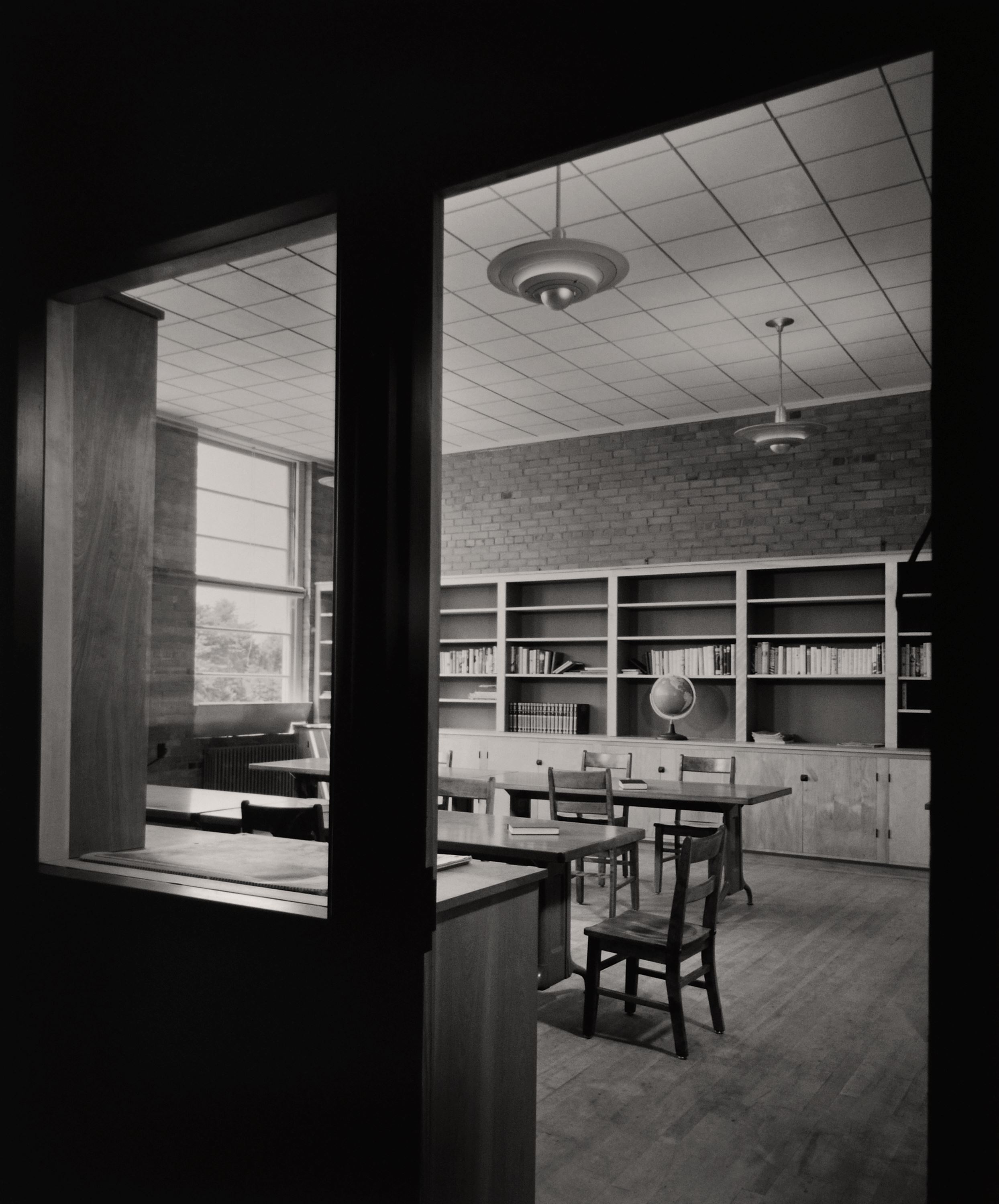

With the arrival of railroads in the 19th century, Portland became a booming transportation hub for people and freight. In 1886, the Portland & Ogdensburg Railroad developed rail facilities at Thompson’s Point where the first railroad repair shops were constructed. Destroyed by fire just a few years later, a 25,000-square foot Machine Shop was rebuilt in 1904 and leased by Maine Central Railroad. During World War II, the government took over the property, and the building was used to store steel for Liberty Ships then under construction. Over the next 60 years, a series of owners proposed several development projects, but none ever got off the ground.

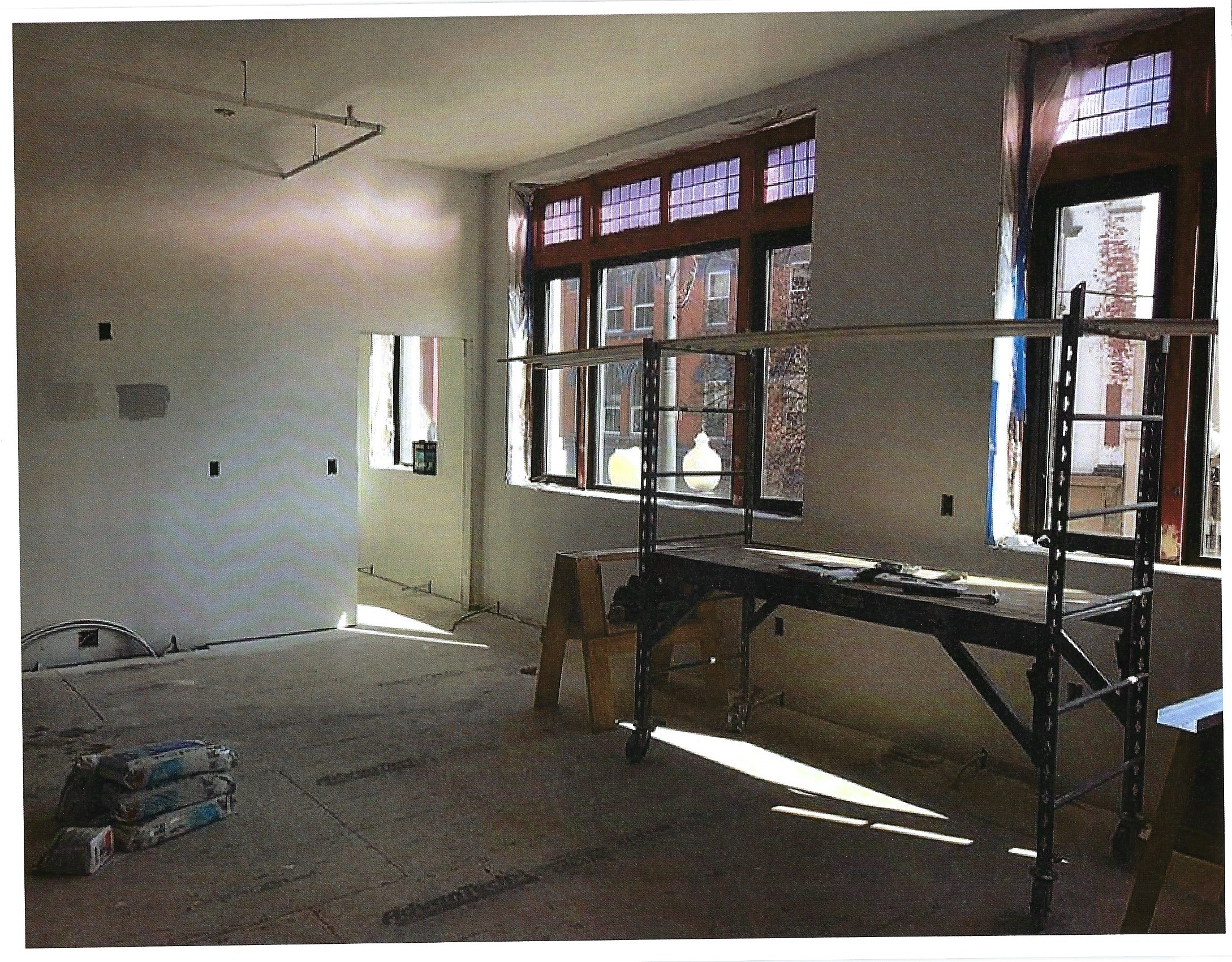

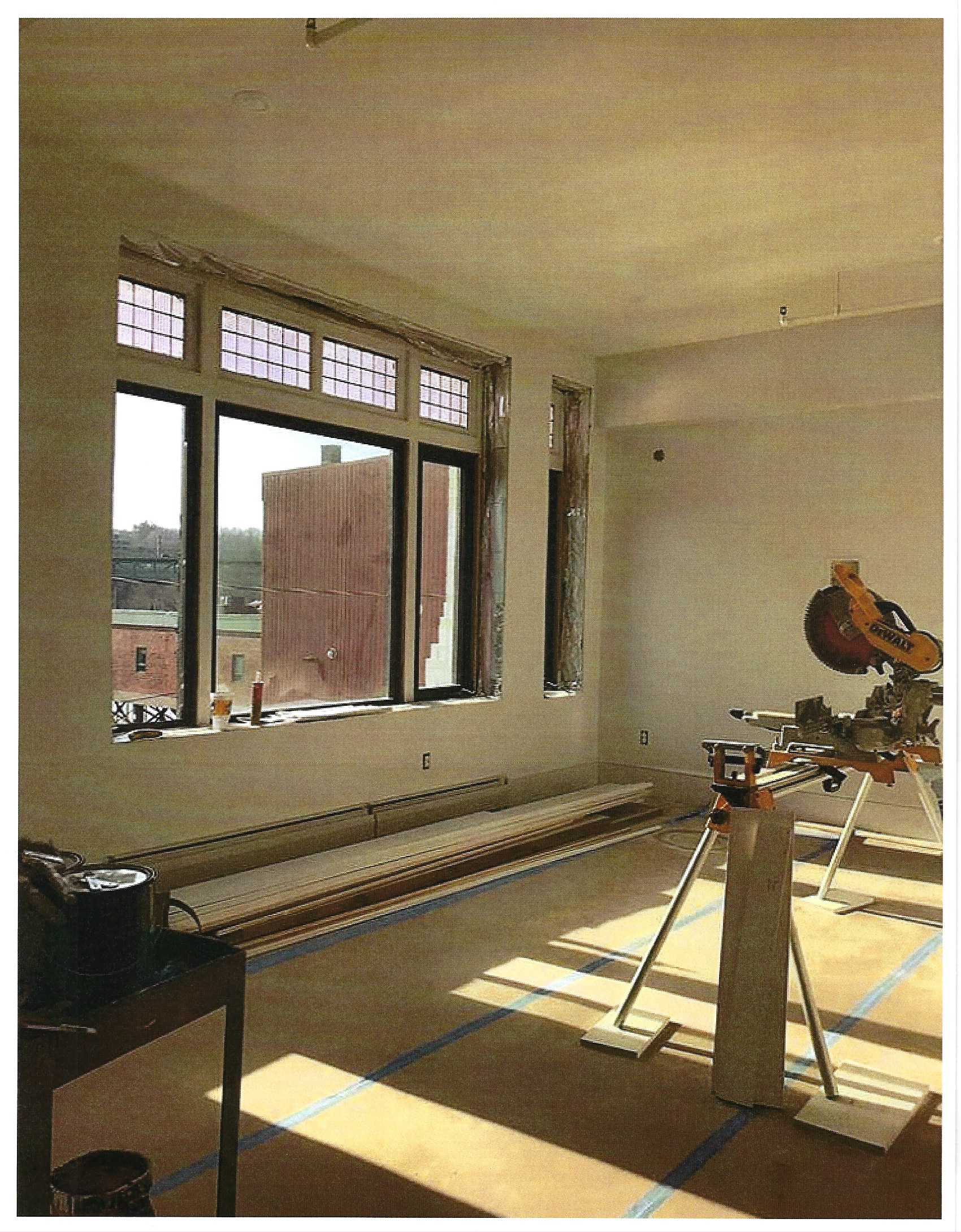

In 2009 Forefront Partners, purchased the property, undertaking the long process of transforming the one-time industrial site into Portland’s most dynamic new district. They re-named the old Maine Central Railroad Machine Shop Brick South. It’s one of just two buildings surviving from the railroad era.

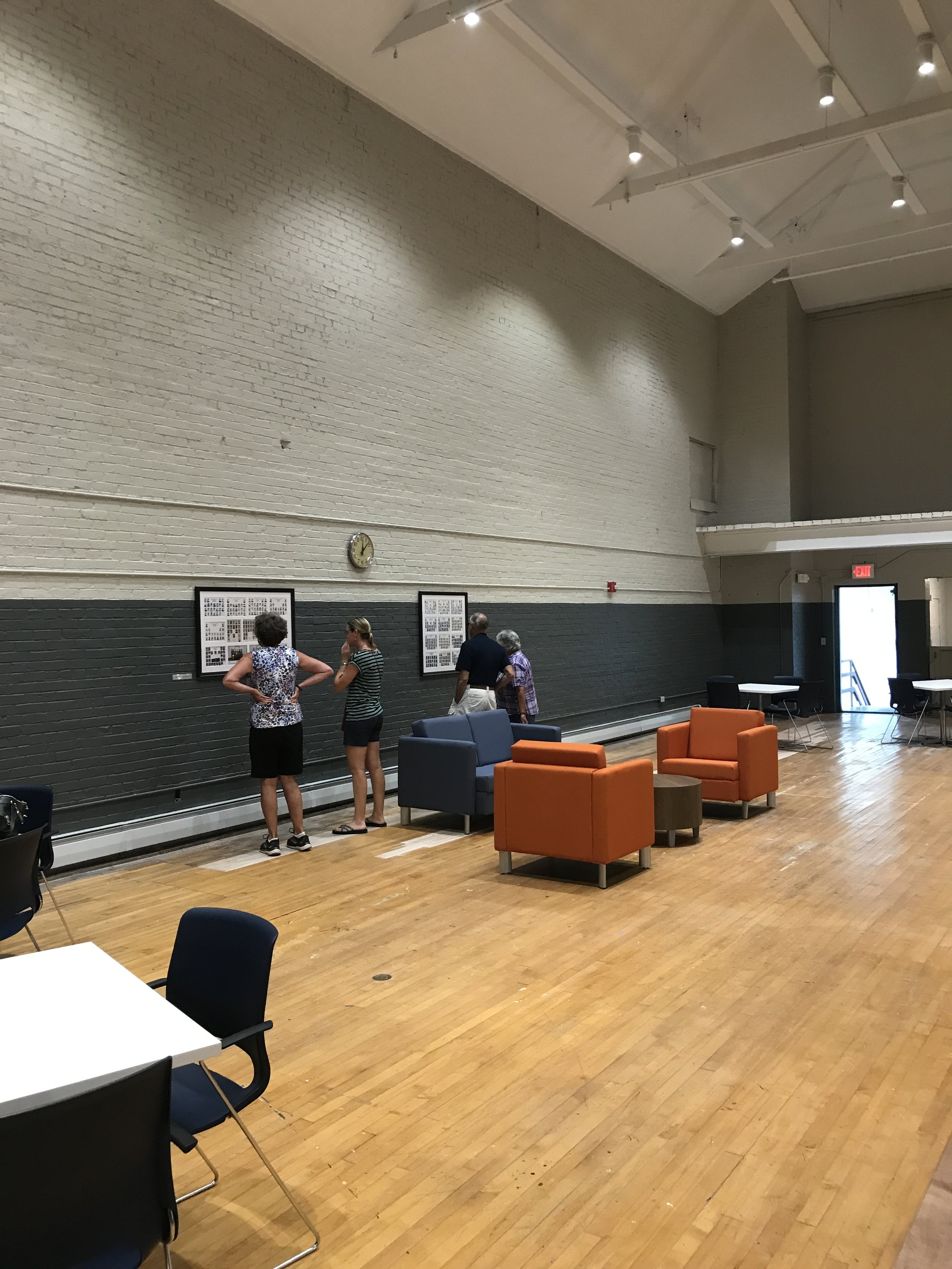

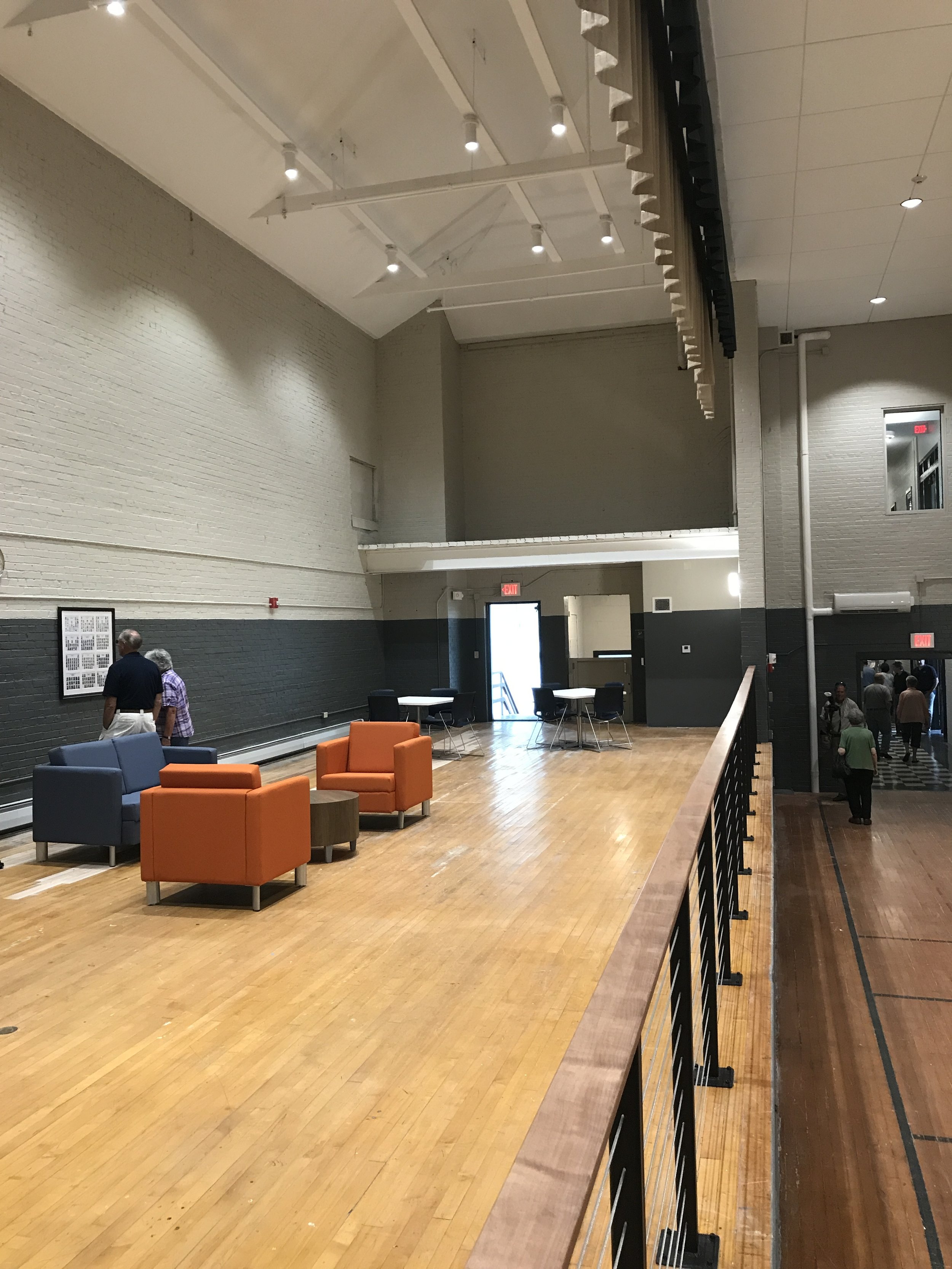

Forefront Partners' goal was to transform the historic Machine Shop into a multi-use event venue, and to preserve the grand vistas and stately character of the space while adding the amenities essential for large, catered events. Care was taken during the development process to preserve the historic and architectural character of the building. Structural reinforcement, roof replacement and a new system of underground utility lines are just a few of the many improvements the machine shop required. In May 2017, the building became the first LEED Core and Shell Gold project in Portland.

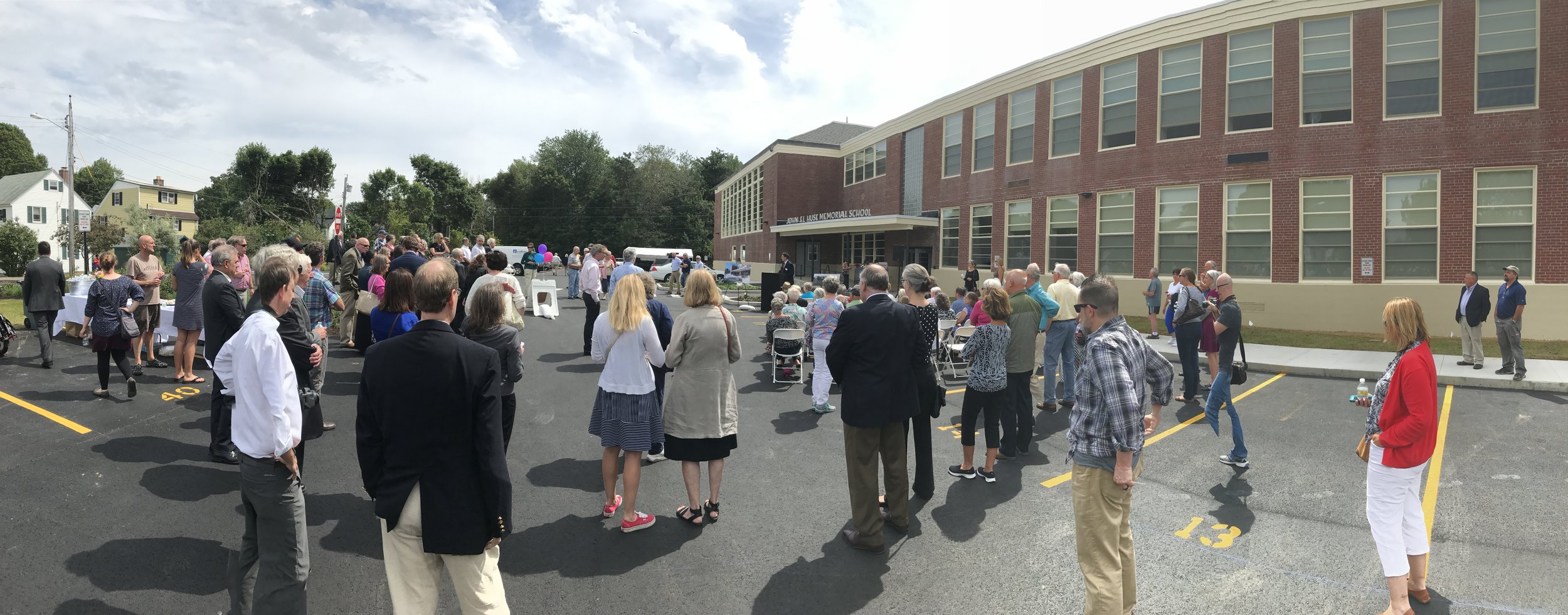

Today, Brick South offers an experience unparalleled in southern Maine, celebrating Portland's rich history and serving as a versatile venue for weddings and trade shows, fundraisers and a variety of festivals. Last year, the Maine Flower Show brought over 16,000 visitors to the site over a three-day period and this fall the building was the site of Maine Preservation’s Annual Gala.

Brick South—a reminder of the city’s railroad heyday-- is on the fast track to becoming a star on the Portland Scene.