Story

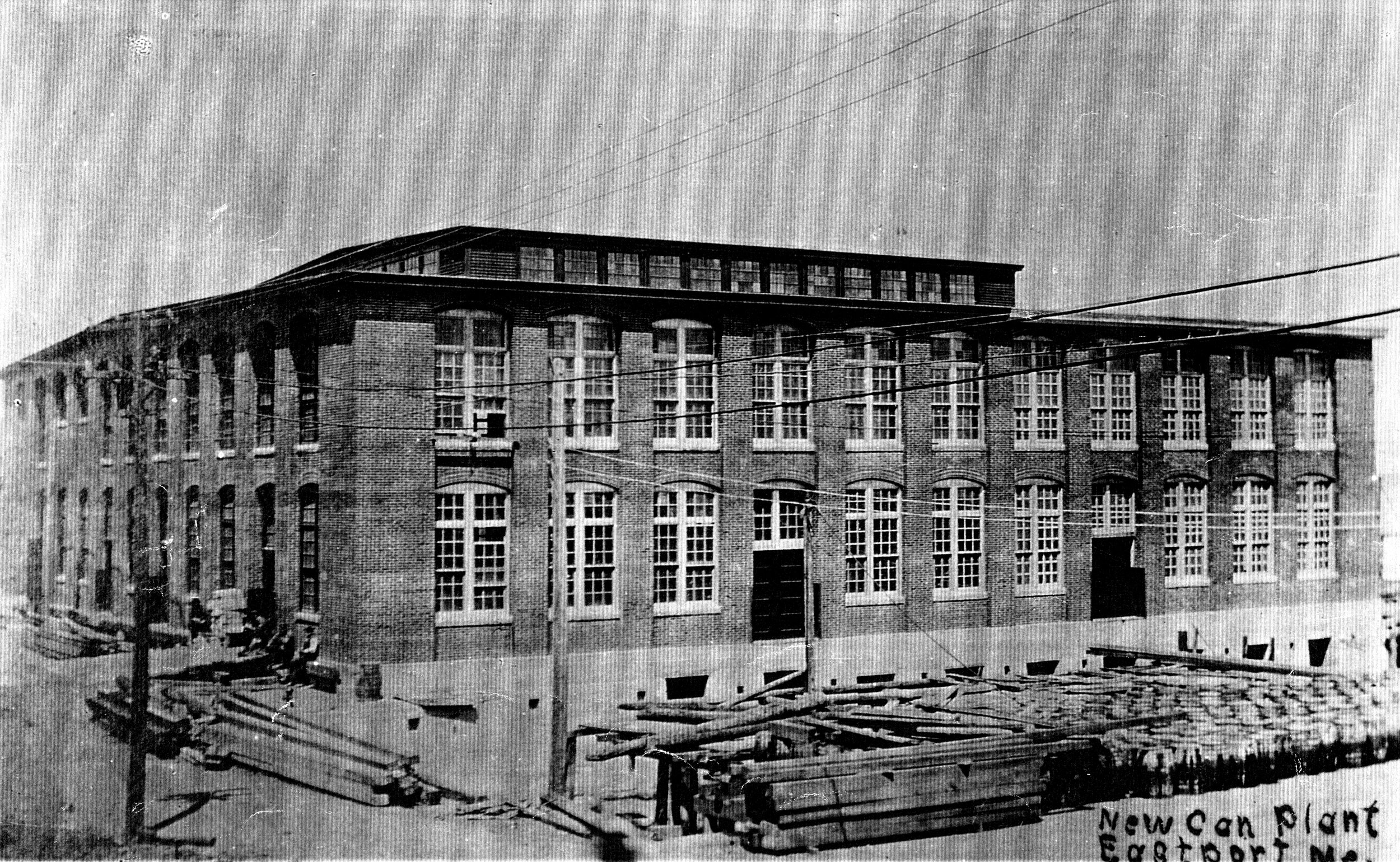

The American Can Company Building is an iconic building located on the edge of Passamaquoddy Bay in Eastport and one of the few remaining structures of the world class Downeast Maine sardine industry. It was erected by the Seacoast Canning Company in 1908, a time when the company was the largest in the industry. The 20-inch-thick brick walls, rough-cut granite windowsills, and heavy timber structural system, designed by Boston engineer Charles T. Main, permitted industrial activity inside, and also signaled a sense of prosperity and permanence for the booming company. Later renamed the American Can Company, the site was home to the Continental Brand of roll key opening can – an innovation that became the gold standard in the global sardine industry.

Threat

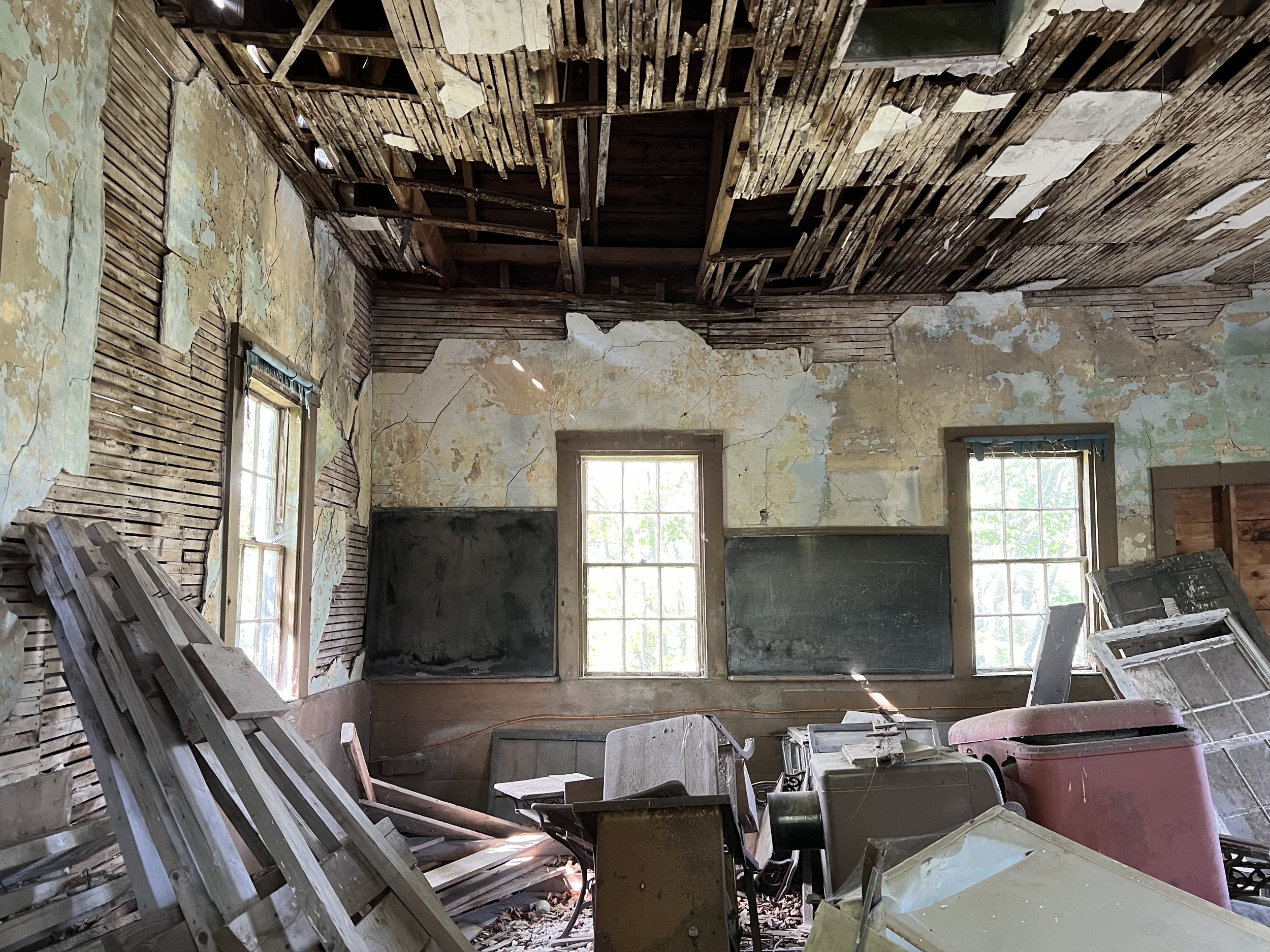

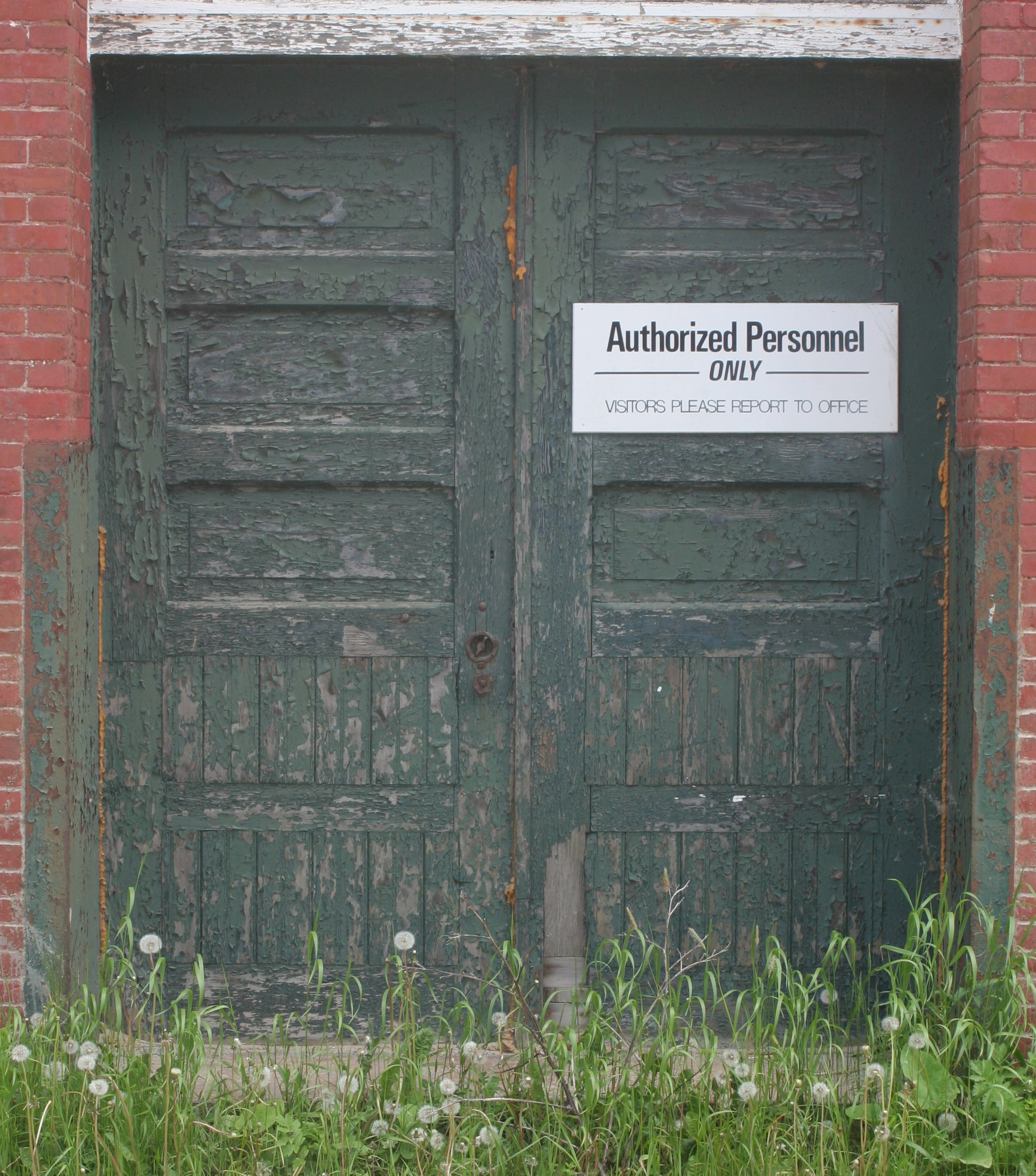

Following the demise of the sardine industry, the 30,000 square-foot building was used as a warehouse for aquaculture. The few improvements that had been made were concentrated on the 139 concrete piers supporting the building. Prolonged neglect of the nearly flat roof and clerestory has meant the deterioration of the roof decking, interior timber structure, and flooring. The brick exterior walls have also suffered from the failing roof and exposure to the elements.

The continued, deteriorated state of the American Can Company building is not from a lack of trying or experience. Meg McGarvey, Linda Cross Godfrey, and Nancy Asante comprise Dirigamus, LLC, owner of the site since 2005. This trio of long-time Eastport entrepreneurs and promoters assembled a professional team and planned early on to revive the building, only to reach dead-ends with highly competitive federal funding programs and roadblocks too often encountered by those looking to make a difference in underserved Washington County. They have a proven track record in Eastport, having rehabilitated the twice-condemned 1886 Mincton Buliding and founding The Commons, which showcases local artists and authors. Their efforts are widely recognized: the Maine Department of Tourism awarded them for “being the spark that launched the restoration of downtown Eastport,” Yankee Magazine named them a Destination Gallery, and the Maine Women’s Fund honored them with a Visionary Leaders Award.

How to Get Involved

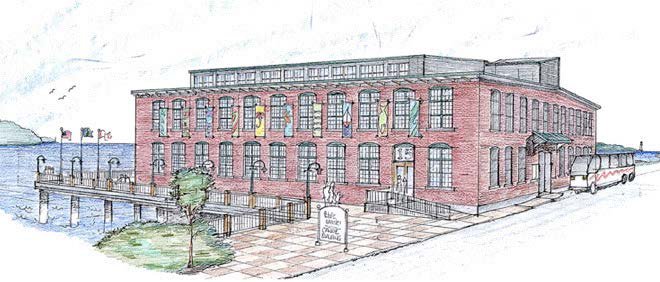

Dirigamus has redoubled efforts to save and reuse this iconic landmark, dubbed “The Lantern on the Pier,” inspired by Campobello islanders across the water who remarked on the resemblance when the light needed for the night shift would emanate through the clerestory windows. When complete, The Lantern on the Pier will include a 12-suite boutique hotel, two large gathering spaces for conferences, exhibitions, and other events, as well as fourteen year-round apartments. The building anchors the south end of Eastport’s downtown, serving as a launch point to visit local cultural institutions like the Tides Institute, sample the local cuisine, or jump into a kayak to explore Cobscook Bay.

The project will have an enormous economic impact on Eastport, creating jobs and year-round housing, fostering opportunities for small businesses, and lodging more visitors. The building’s inclusion in the National Register Historic District means the redevelopment will be substantially supported by State and Federal Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credits. Without financial partners, the future of the American Can Company Building will only grow more uncertain. The groundwork has been laid for the American Can Company Building redevelopment, and now the project needs investors to make this catalytic project for Eastport and the regional Downeast economy a reality.

Check out this informational brochure to learn more about The Lantern on the Pier project and Eastport, Maine.

Learn how you can become a part of the restoration by speaking directly with a member of the development team:

Linda Cross Godfrey, Project Facilitator/Communications Contact

Meg McGarvey, Owner’s Representative/Construction Team Contact

Nancy Asante, Online Data/History Contact

207-853-4123 | info@lanternonthepier.com