The Story

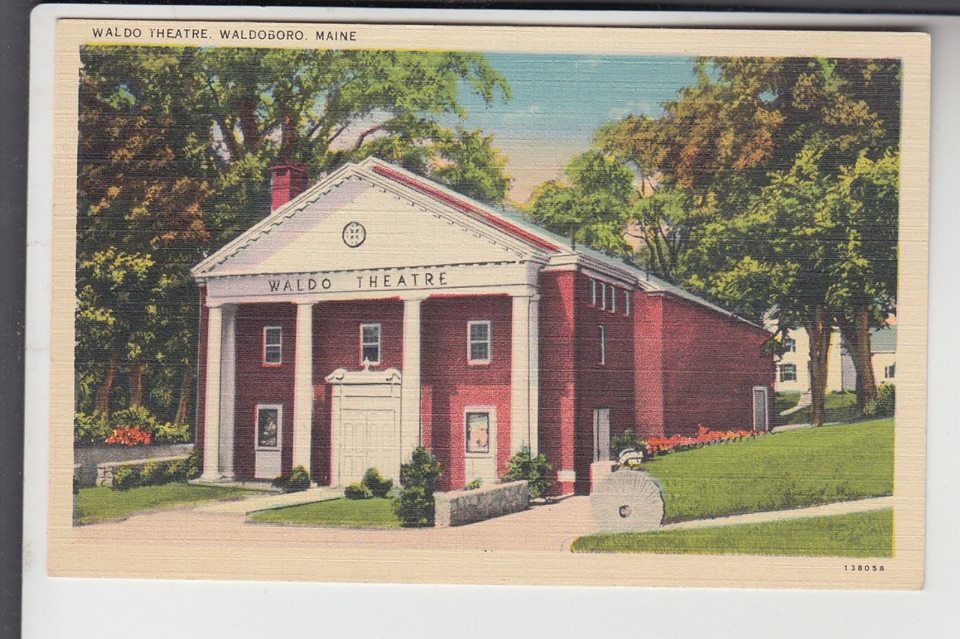

Wiscasset, whose gateway signage states, “the prettiest village in Maine,” is often recognized as a community of beautiful 18th and 19th century historic houses and a charming commercial district along the Sheepscot River. Its dynamic and diverse residential architecture is the envy of many Maine communities and is one of the area’s biggest visitor draws.

In 1973 Wiscasset was the first historic district in Maine listed in the National Register of Historic Places and the architectural importance of this community has long been recognized. The listing itself states, “The constant stream of tourists pausing before these houses reflects the importance of preserving Wiscasset's best natural resource.” Only recently, however, has Wiscasset passed an historic district ordinance and established a Historic District Commission (HDC), providing local protections and guidance to ensure the longevity of the district.

The Threat

After just one complaint from a homeowner who had demolished an historic fence without review from the HDC, the City of Wiscasset is now considering eliminating the entire Historic District Commission. The ordinance was designed to specifically, “prevent, without prior review, the demolition or removal of significant historic buildings or structures within designated districts or designated sites or landmarks and other significant design elements.” The ordinance was passed in 2015, and the commission has only been in place a year. The intent of the commission is that: “The heritage and economic well-being of the Town will be strengthened by preserving its architectural and historic setting, conserving property values in unique areas, fostering civic beauty, and promoting the use of historic or architecturally significant buildings for the education and welfare of the citizens of the Town of Wiscasset.” It is natural for new commissions to experience growing pains, and one individual complaint should not dictate the future of an entire historic district.

The Solution

Studies have shown that Historic District Commissions increase property values, provide insights to property owners undertaking the difficult job of rehabilitation, and ensure the important and character-defining elements of landmarks are safeguarded for all property owners, residents and visitors. The Wiscasset HDC has not yet had the opportunity to educate the citizens of Wiscasset to the many advantages of commissions, including federal and state grant funds, but is already planning new online resources for property owners in the district and a new online application that should make the entire process easy to navigate. Many other communities across the state have had such commissions in force successfully for many years and others are looking for progressive and straightforward ways to ensure their heritage is celebrated and maintained. We encourage Wiscasset to continue the HDC to allow the community to strengthen its property values, retain the attractive features that attract so many visitors and residents and remain a model for historic preservation in Maine.