In 1771, Dr. Silvester Gardiner established St. Ann’s Church, which included the region’s only meeting house and churchyard where early settlers were buried. The churchyard includes the graves of Revolutionary War veterans and families tied to the area’s pioneering businesses, including the 1791 gravestone of Dorcas Gardiner and Dr. Gardiner’s son, William, who died in 1787. By 1823, the churchyard was so full that burials were restricted. The 1840s opened space as families moved graves south to the more fashionable Oak Grove Cemetery.

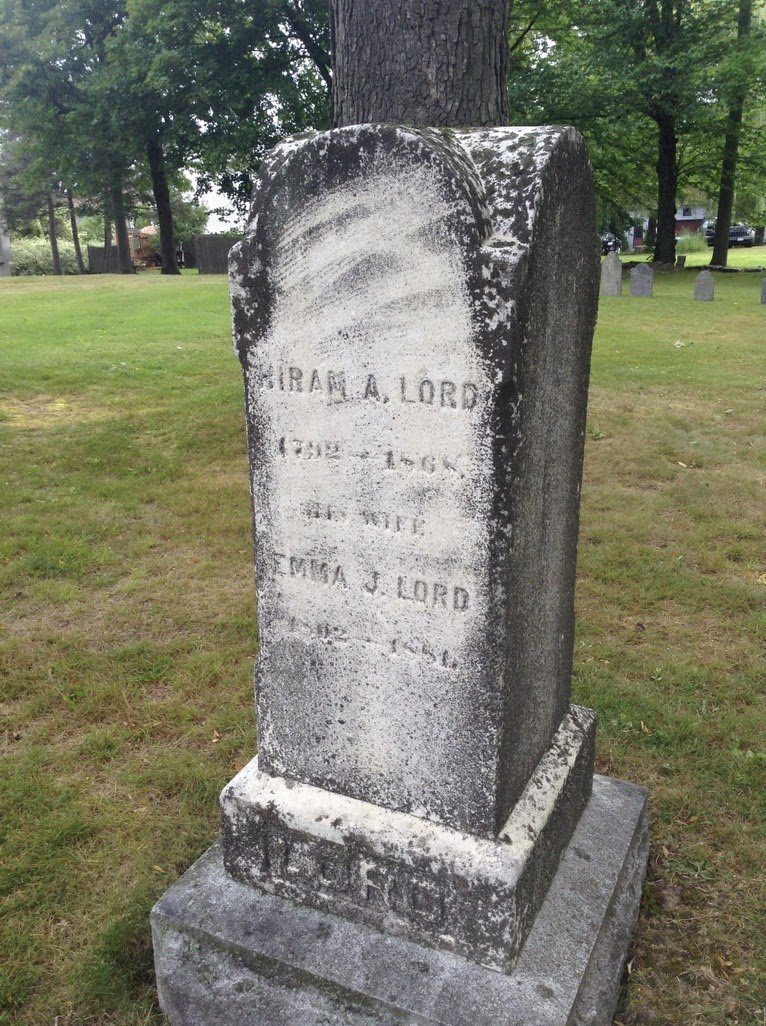

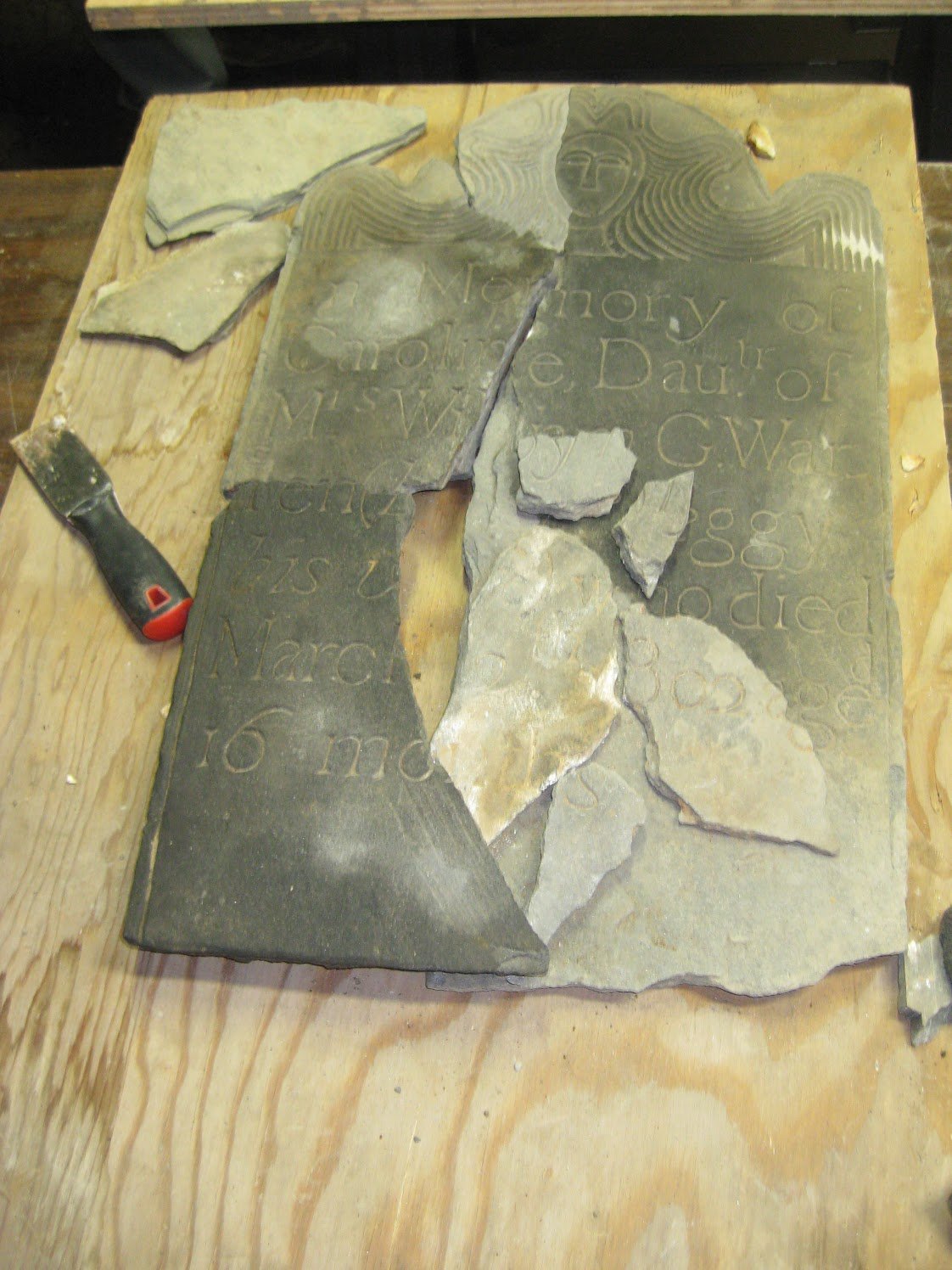

Unfortunately, the diminishing interest in the churchyard did not bode well for the existing burials. Town records indicate that 65 gravestones stood in 1911, a time when the churchyard was no longer used and had fallen into disrepair. Fundraising efforts in 1889 and 1924 to improve the churchyard fell short and did little to inspire action. By 2014, only eleven burial stones remained. Another unsuccessful effort gathered and recorded 30 fallen and broken stones and graded the yard to locate others. Another 21 gravestones and many footstones were relegated to the church basement, generally forgotten, undocumented, broken and hidden.

Enter William “Bill” King, Jr., who first encountered the churchyard in 1987 while locating the graves of his Gardiner family ancestors, first cousins of Kennebec Proprietor, Dr. Silvester Gardiner. When he returned to the churchyard fifteen years later, Bill found the remaining stones upended, broken and flat. Bill shared the concerns of Christ Church parishioner and historian, Jody Clark, who recruited fellow-parishioner and groundskeeper, Hank McIntyre, and Gardiner Public Library’s Special Collections Librarian, Dawn Thistle, to restore the churchyard. Together, this determined team worked for seven years conducting needed research and completing physical restoration work.

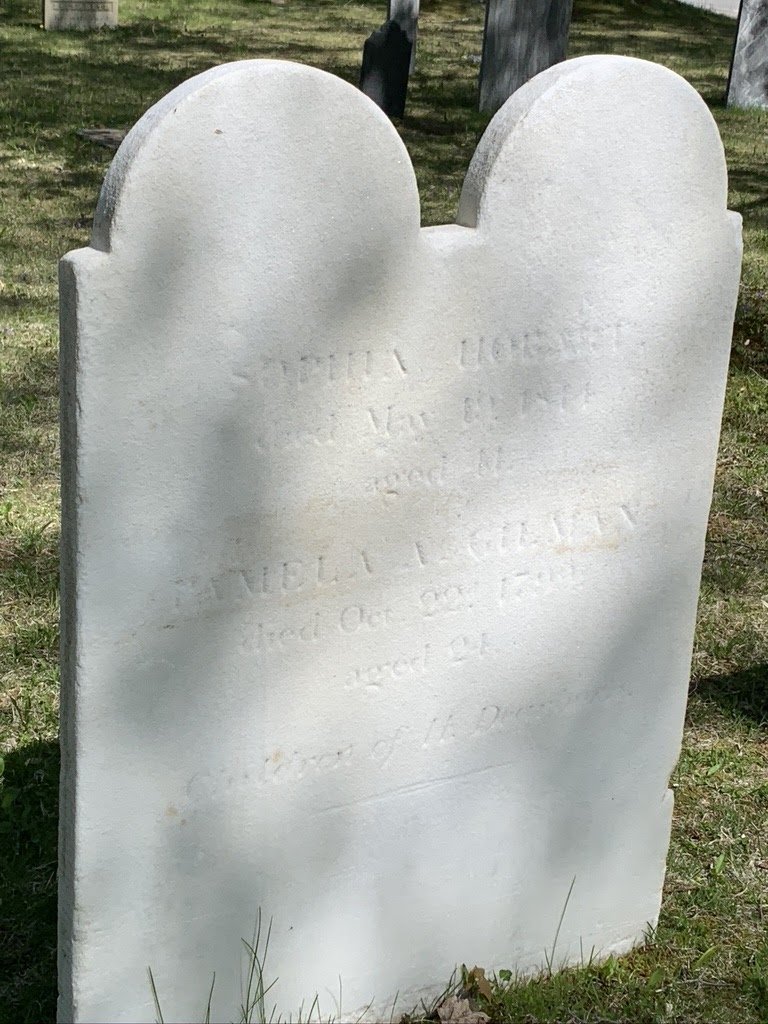

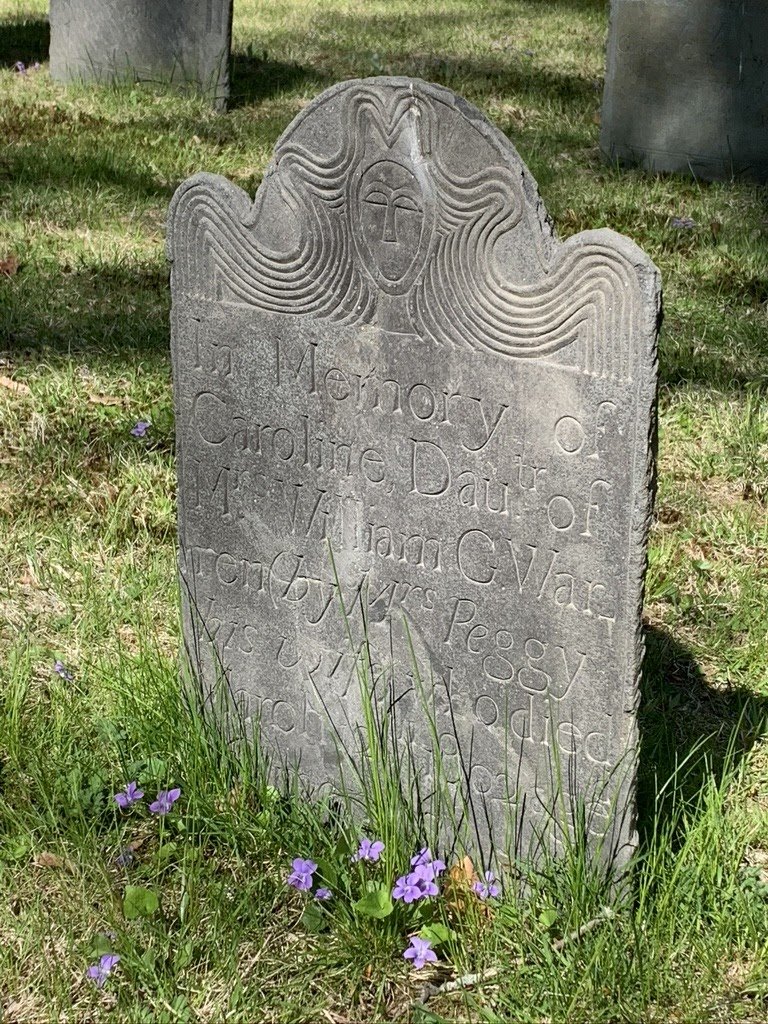

Volunteers initiated re-placement of stones, working from archival research, intact stones, and two photographs pre-dating stone-toppling. Placement was confirmed by discovering matching material underground, and broken stones were repaired and cleaned. The team credits the project’s success to the literal heavy lifting by friends, family, and parishioners of Christ Church, which owns the churchyard and enthusiastically supported the project. The restoration of the physical grave markers was guided in part by Cheryl Patten of the Maine Old Cemetery Association (MOCA).

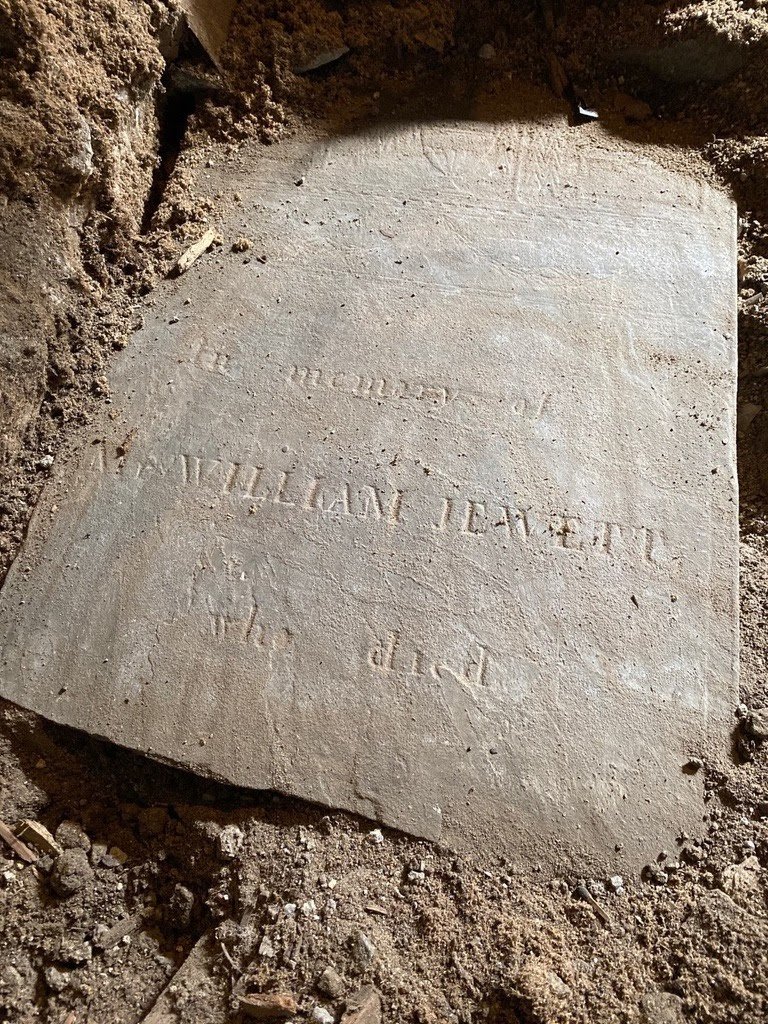

The local group also hired New Hampshire firm, Topographix, to conduct Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), which aided in grave identification. They identified fifty anomalies, outnumbering remaining stones. The group also discovered the stones in the church basement – one was even found supporting the church’s foundation. When missing, new bases were cast or cut from stone material. Volunteers epoxied stone breaks, filled cracks, repaired chips, and even re-carved inscriptions. Some 50 gravestones and 17 footstones were cleaned and placed, returning them to historic locations, restoring the historic burial ground.

The successful efforts to restore St. Ann’s Churchyard is both a cause for celebration and a call for action to reflect upon the importance of preserving the hallowed grounds that dot Maine’s landscape. As Bill King explains, “they are a very important repository of our history, holding the last remains and documentation of our founders and builders of our Maine culture and communities.” Along with completion of the project, the team also celebrated another occasion, reconsecration of the churchyard.