If you’ve been to downtown Lewiston lately you have seen the amazing renaissance underway, and likely noticed the four-story, white brick building that rises above Lisbon Street. Designed by J. Coburn and Sons, a local architecture firm, the Osgood Building and adjoining McGillicuddy Block are the only two surviving commercial structures designed by Jefferson Coburn himself. Typical of Coburn’s eclectic styling, the building was commissioned by Jeweler H. A. Osgood and clad with white English glazed bricks; no other examples of this construction material are known in Maine. Initially the offices of law firm Berman and Simmons occupied the second floor, but as the firm expanded it eventually purchased the entire building. The Osgood Building has now served as firm headquarters for over 100 years.

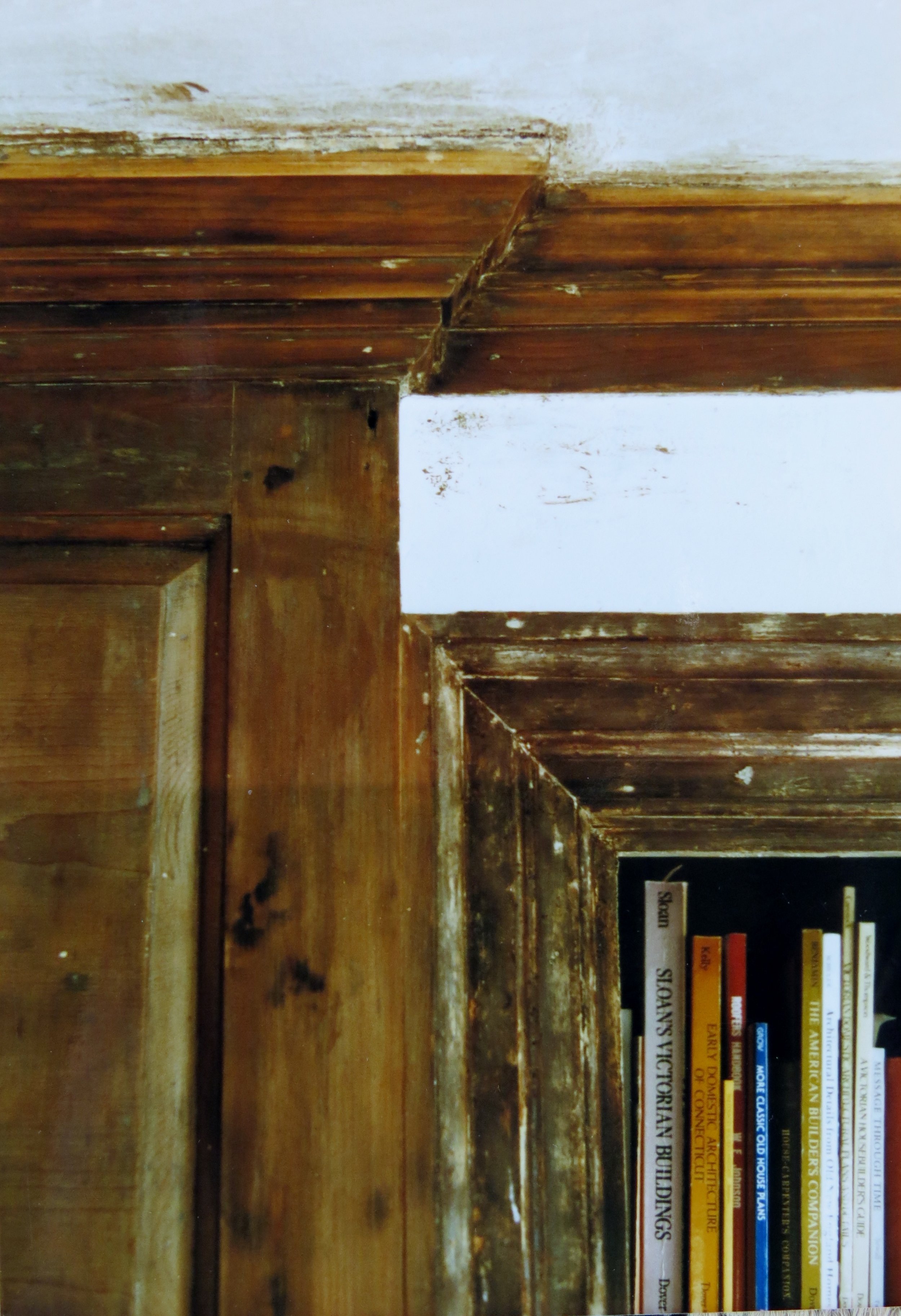

In previous work on the façade, an inexperienced contractor made the huge mistake of removing the glazing from approximately 1,500 bricks, then applying paint to match the surrounding ceramic bricks. The painted bricks began to pull away from the façade, and some even fell off. In another unfortunate change, the building’s brick entry was altered from its original configuration and replaced by a narrow opening which made it difficult for people with wheelchairs and other mobility aids.

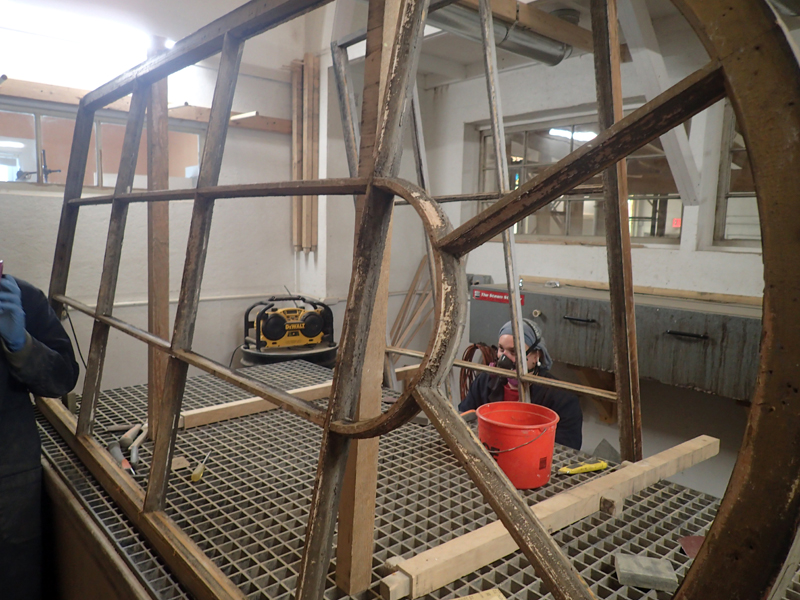

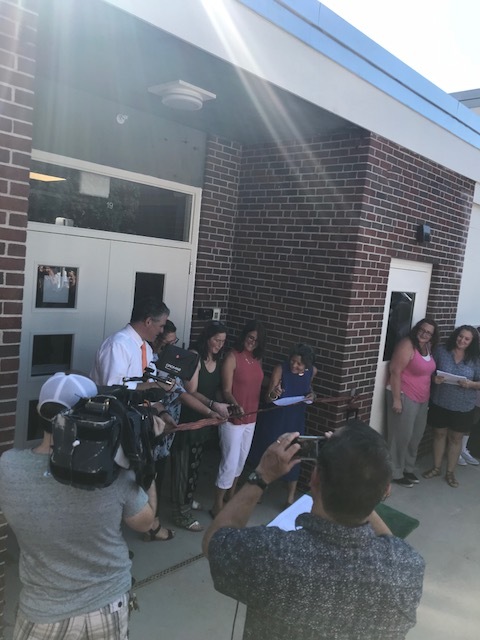

Berman and Simmons was committed to staying in the building. However, the firm wanted to modernize the space to better accommodate current needs while also celebrating the building’s history. Working closely with SMRT Architects, P&G Masonry, Warren Construction Group and tax credit consultants Epsilon Associates, Inc. the firm identified replacement of the 1500 damaged, painted bricks as a priority. The project team experienced a particular challenge when they learned that the original white glazed brick was no longer manufactured in England. Fortunately, the Glen-Gery Hanley Plant based in Texas produces a very close match. Enough bricks were purchased so that all 1500 damaged bricks were replaced and repointed. Other restoration work included new windows facing Lisbon Street that are similar in design to the original storefront windows and reconstruction of the original entry and the installation of ADA compliant entrances.

The Osgood Building was restored in a sensitive manner using the effective Maine Small Project Rehabilitation Tax Program. Not only did the project save and revitalize a prized landmark on Lisbon Street, it added tremendous energy to Lewiston’s ongoing renaissance.