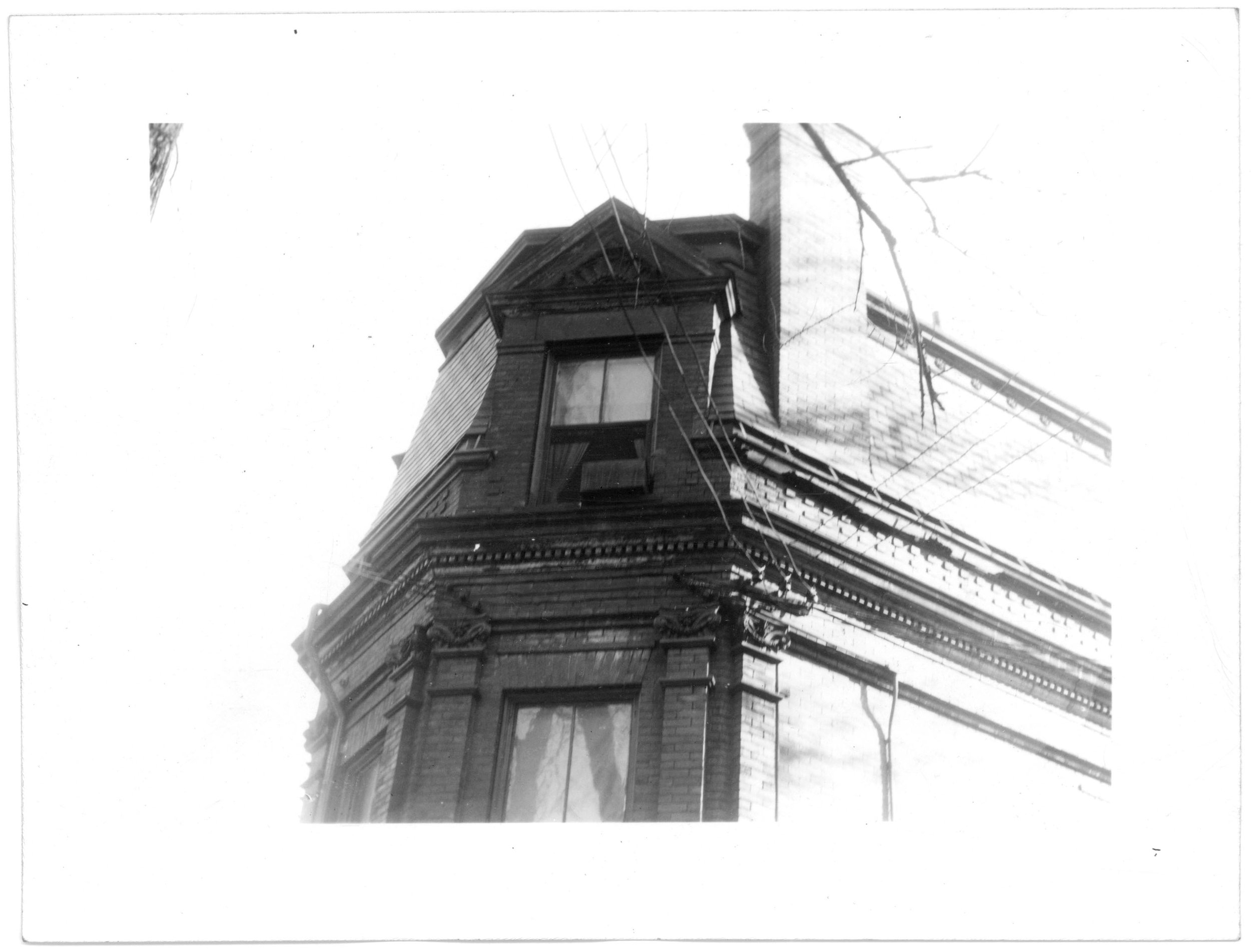

The George S. Hunt Block at 660 Congress Street is a designated landmark in a local historic district, and a contributing building to one of Maine’s national historic districts. Built in 1886 and designed by noted Portland architect Francis Fassett and his associate Frederick Thompson, it is a prominent example of the once-popular Queen Anne style.

In 2011, the previous owner abandoned plans to rehabilitate the building in the wake of a destructive fire. They had demolished the building's interiors at the behest of their engineer, leaving only the historic facade and roof, which had been severely damaged by the blaze and suffered from the effects of years of deferred maintenance.

A complete transformation began in December 2011 when 660 Congress was purchased by, Kenn Guimond, who served as both the developer and general contractor. His contributions to the project were singular. Not only did he meet and exceed the Secretary’s Standards for Rehabilitation of the exterior, but his commitment to design excellence underscored a respect for the quality and history of the original building. Where others might have seen an opportunity for shortcuts, he chose to pursue a thoughtful rehabilitation, with a spirit of integrity and attention to detail that honored the spirit of 19th-century building practices.

Guimond’s initial challenge was to envision the interiors without any existing documentation reflecting their original design. Guimond returned to what remained of the building, the historical facade, and traced the silhouette of the mansard roof with gently curving walls. At the ceiling, the expansive volume of the roof is revealed with dramatic light coffers that bring light into the spaces through skylights and hidden architectural lighting.

In other areas, fragments of history such as arched doorways, fireplaces and brickwork were left untouched. The new residential entrance features a blackened steel stair with solid white oak treads, fabricated by a local Maine welder. Many of the improvements are hidden from view, such as new HVAC and utilities, code compliant structural work, and upgraded environmental and life safety systems. The facade was the most important historical aspect of the project and was meticulously rehabilitated. New copper roofs were installed, and unsightly downspouts were returned to their original concealed brick pockets. The pressed tin frieze and dentil ornamentation were carefully restored on site, and rotted wood storefront window frames were replaced in kind. This was accomplished on a logistically complicated site with limited private property available for staging.

The team approached the $2M redesign with a vision to revitalize the landmarked facade and modernize the building’s interior, allowing the spaces to flow fluidly together. The result is a building aware of the past, but not bound to it. The 7,500 square foot structure was completed in 2016, and includes a pair of two-bedroom apartments, and a light filled commercial space on the ground floor with a spacious basement retail space.

The time and effort invested in the rehabilitation has created a building in dialogue with its own history, reflecting the commitment to design shared by the people involved in its past and present.